When drummer, composer and bandleader Mike Reed isn’t playing music he spends much of his time watching others making it. But he also observes audiences. As a concert and festival organizer, he’s informally noted the interaction between performer and audience for years, and while his rapidly expanding discography makes plain he privileges art above all else, his awareness of the listener is always present.

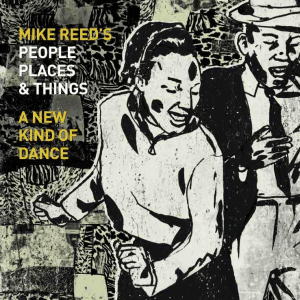

A New Kind of Dance, the sixth album by his long-running quartet People, Places & Things presents the same deft interactive rapport between alto saxophonist Greg Ward and tenor saxophonist Tim Haldeman; the same crisp rhythmic drive provided by the leader and bassist Jason Roebke; and the same indelible mixture of bluesy depth and measured freedom as its superb predecessors. A New Kind of Dance advances the boundaries of the quartet’s repertoire further than ever and adds two guests to the mix: pianist Matt Shipp and trumpeter Marquis Hill.

“I wanted to challenge the quartet situation and make things slightly more dimensional, such as having three-part horn arrangements or having another harmony/rhythm instrument to dictate the path,” Reed said in a recent news release.

“I thought Matthew Shipp would throw some curve balls at the rest of the band. He has some elevated perspectives on improvising, while not standing on top of an ivory tower. His improvising is very humanistic, but he has no problem cutting people down to size, so that everyone can operate on a level playing field. Marquis seemed to be the right choice to find the right trumpet blend with Greg and Tim. His tone can keep things very centered, and he plays with a purpose.”

Here is an older video of People, Places & Things in action.